Commodore History

There have been many questions about Commodore before they

went into liquidation. How did they start? What drove them to sell

their own specially designed system? How could they make so many

mistakes and never learn? Although I can't answer all these

questions (especially the last one), I can reveal what Commodore

were before the Amiga.

The tale begins in Lodz, Poland during 1927 where Jack Tramiel

was born. It was a time of great change for the country, in 1939,

when Tramiel was just 12 years old the German army invaded. Through

sheer luck, he survived the Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen death camps

to be one of only 970 of Lodz's 200,000 Jews to survive the

Holocaust. In 1947 he moved to New York, drawn by the idea of

running his own business in the country that could turn anyone into

a millionaire. In 1954 he decided to supplemented his army career

by fixing typewriters that had become jammed at the local base.

Tramiel realized the demand that there was for proper repairman

leaving the army and setting up his own typewriter repair business

in the Bronx, whilst working as a cab driver at night. The business

did not make a fortune overnight but managed to make a deal with a

company in Czechoslovakia to assemble their brand of typewriters in

Canada. Recognizing the opportunity he moved to Toronto and set the

foundations of what would become Commodore International. As the

company gained more experience and wealth in this industry Tramiel

realized that his profit ratio could be increased by cutting out

the middle man and selling his own typewriters, rather than

producing them for someone else. However, money was getting tight

as cheap Japanese models were overtaking the market. Realizing that

he could not compete with the swarms of foreign companies now in

the market, he moved the company into the relatively new market of

adding machines. Tramiel's market insight had taken the company

into a new direction.

In 1962, the company went commercial, calling itself Commodore

Business Machines, Canada. This company was led by Tramiel, with

the banker and chairman role being given to the president of

Atlantic Acceptance Corporation, C. Powell Morgan. Morgan was to be

condemned three years later by a Canadian royal commission for his

defiance of all accepted business practices" and acts of "rapacious

and unprincipled manipulation. He died of Leukemia before this

could be taken to court. The commission also examined Tramiel and

his company, and although they suspected Tramiels involvement, they

could not really prove anything. Unfortunately, the bad publicity

caused by this incident did not help Commodore, which made a

continued loss.

Commodore was saved from an early grave by a Canadian investor

by the name of Gould, Irving Gould. A name that has ingratiated

itself to many Amiga owners over the years in its own "particular"

way. Gould agreed to take a stake in Commodore, in return for the

position of Chairman. These events helped Commodore for a short

time, but it became increasingly obvious that the adding machine

business was becoming tighter, as the Japanese again came out with

cheaper, better models. Gould suggested that Tramiel should get

experience of the market situation in Japan. Whilst he was there he

saw the new electronic calculators. Commodore quickly moved from

the restrictive adding machines on to calculators, and made its

move into the electronics business.

After a few months Commodore began to makes a profit pioneering the

first electronic pocket calculator on to the market, finding itself

at the forefront of the first electronic boom. This victory was

short-lived as Texas Instrument; Commodore's chief chip supplier

launched their own brand of calculators, at a fraction of the cost

of Commodore own. The year was 1975; Commodore made a loss of $5

million on sales. Tramiel and Gould learned a major lesson- DO NOT

rely on outside suppliers. Tramiel later commented,

From there on, I felt the only way to continue in the

electronics business was to control our own destiny.

It was a lesson that Amiga owners are suffering even today. The

market had suddenly closed behind Commodore and they faced another

major crisis. Again, Gould came to the rescue with a $3 million

loan. This allowed Tramiel to take over the struggling MOS

Technology, Frontier, and MDSA in 1976. This gave Commodore the

power and experience to produce their own electronics.

In 1975 Chuck Peddle quit his job at Motorola and went into

business for himself, developing the 6501. This was an advancement

on the 6800,a chip Peddle had been designing in his previous job.

The processor's were similar enough to be pin-compatible with each

other. A fact that infuriated Motorola- even though they were not

able to run the same software the idea of a plug-in expansion led

the company to sue MOS Technology for millions of dollars.

For quite some time Tramiel had been keeping an eye on this

unfolding situation and offered to buy MOS Technology. Peddle

agreed and the company became MosTek. The purchase was a sound

one. Peddle convinced Jack Tramiel to look into the

possibility of a desktop computer, using MosTek's advancement on

the Motorola 6800, called the 6502. It became the most popular

processor of the 1980's, ranging from the Apple I to the NES.

Tramiel felt cautious about developing an entire system from

scratch and offered to buy Apple. Steve Wozniak was tempted but

felt Commodore had not offered enough for the company and wanted

$15,000 more. Tramiel refused- a horrifying thought that may have

resulted in the Mac never existing altogether!

Disappointed but anxious to get into the computer market, Tramiel

set Chuck Peddle the task of developing a computer. This resulted

in the development of the PET (the idea being that it would serve

the user, like a dog fetching the newspaper). It was first shown at

the Chicago Consumer Electronics show in 1977. After the show the

name's meaning was changed to an acronym of Personal Electronic

Transactor so that people would take it seriously. Working for 3

days without sleep, Chuck Peddle was under great pressure to

actually finish the machine for the show. Enthusiasm was high, soon

Commodore had over 50 calls a day from dealers desperate to supply

the demand for the machine. Commodore made sure that reputable

dealers, who could actually sell the machine and repair faulty

ones, only sold the system. As demand for the PET grew, so did

Tramiels thirst for profits. He arranged a deal between Commodore

and all of the major retail chains. The dealers were in direct

competition with the big boys. Tramiel had made yet another

mistake, by offending the independent dealers that had originally

sold the Commodore machine he made many enemies, who would never

sell another Commodore machine again. Many of those that remained

had to forfeit their "customer care" to compete. The PET had been

adopted as the computer of choice for many schools, years before

the standard was set by the government, but Commodore still wanted

to dominate the home market. At the time only the ZX81, Sinclair's

baby that could have stopped them. So, Commodore moved into the

home market launching the VIC-20. Although relatively basic in

design the machine was sold cheaply and had a great deal of

software support, beating even the ZX81 in popularity. The low

price point and cheap design tarnished Commodore's reputation and

the machine became a toy in the public eye. Tramiel struck back at

competitors with a string of price cuts. At its peak the Vic-20

sold for just $55, and were produced at a rate of 9000 per day.

The Commodore cash machine went into overdrive as millions of

people jumped onto the bandwagon. The Vic 20 was superseded by the

Commodore 64 - a comparatively expensive system (£350) -

launched during 1982. Commodore had learnt from their earlier

mistake, gaining a percentage of the C64 sales, through the

ownership of the 6502 CPU. However, the European market was slower

to accept the machine as a result of the high price demanded in

comparison to the alternatives. Its closest rival, the Sinclair

Spectrum, was almost half the price and appealed to the game

player, rather than the home office.

Unconcerned by the slow sales, Commodore launched a low end

version, the C16 and the Plus/4. Aimed at the home market, they

used the same processor as the C64 but reduced the memory back down

to 16K. Though technically inferior, they sold reasonably well for

a brief time but was unable to gain the popularity of the earlier

Vic 20.

As time progressed, the cost of manufacturing the C64 fell. In

conjunction with the strong software market that had developed and

the falling cost of the IBM PC, Commodore abandoned the notion that

the C64 was a business machine and aimed it at the game market. In

a brief, but entertaining battle, the C64 overtook the Sinclair

Spectrum in the market, exceeding expectations.

Events were not as happy behind the scenes, as Commodore boss,

Jack Tramiel became increasingly unhappy with his lack of control

over his company. In a statement released during January 1984,

Tramiel said, "personal reasons prevent my continuing on a

full-time basis with Commodore." He quit Commodore and bought

the troubled Atari Computers from Time Warner with the intention of

getting revenge on his former company by beating them to the 16-bit

marketplace. Tramiel saw this opportunity in the troubled Amiga,

Inc. Company, whose machine, the Lorraine was more advanced than

any other currently on the market. He quickly made a bid for the

company but did not want to pay the full amount expected, by

constantly dropping the amount he would agree to pay. Tramiel

wanted the technology created but he had no interest in the machine

or its creators, making the Amiga Inc. very wary of him. Meanwhile

Commodore had not let their technology become stagnant; at the

Hanover fair in Germany during 1984 Commodore International

launched their Commodore PC and the Commodore Z8000. Whilst the

Z8000 bombed, Commodore made some money on the PC. Not as much as

their 8-bit line but enough to make it profitable. They were also

producing a Unix compatible machine completely oblivious to the

events going on at Atari. At the last minute, less than two days

before they were to sign with Atari the troubled Amiga Inc. was

swept up from under the nose of Tramiel by Commodore, gaining the

technology and its creators in one swoop and began to create the

Amiga 1000.

Commodore were still reeling from Tramiels' exit. His

replacement, Marshall F. Smith initiated damage control as the

computer industry collapsed in on itself, cutting the payroll by

more than 45%. Although the company had an impressive $339 million

in 1985 Holiday revenues, it made only $1 million for the quarter

after paying off around a quarter of its bank debt. Commodore's

woes continued during 1985, as it lost $237 million. At this point

they may have gone to an early grave but for a one month extension

on loans granted by banks. This allowed time to reap the rewards of

the company's second-best Holiday sales, as the 8-bit line sold out

in many stores.

In March 1986, Thomas J. Rattigan replaced Smith as Commodore's

CEO. He cut the payroll further and three plants were closed in

five months. New controls were added in the finance department to

prevent the sloppy reporting that had undermined Smith's

leadership. By March 1987, Commodore had caught up on its loans,

posting a $22 million earning in the quarter ending December 1986.

It also had $46 million in the bank, the most profitable since

1983. With the company recovering from the crisis of the early

eighties and finally shaking off the ghost of Tramiel they moved on

to the next generation. However, troubles were not behind and the

companies financial edge was slowly eroded. Their only hope lay in

the Amiga, that quickly became known as the "save-the-company

machine."

To his credit Tramiel had always been a sound businessman,

having jumped from what he thought was a sinking ship. His rising

star was frustrated when Commodore wrestled the Amiga Corporation

from his fingers. Determined not to let his former company win,

Tramiel set about creating their own machine using off-the-shelf

parts and release it before the Amiga hit the shelves. The Atari ST

sold for nearly £600, compared to the A1000's £1500,

allowing the Atari machine to outsell the A1000. Most Amiga games

of the time were Atari ports as well, which initially made game

players more interested in the Atari. Problems were also abound in

the board room as Rattigan was replaced by Chairman Irving Gould.

His departure was unclear with Commodore reporting $28 million in

profit, Rattigan claimed that he was forced out by personality

conflicts with Gould due to Rattigan getting credit for the

company's turnaround. Gould argued that the comeback in the U.S.

was insufficient compared to its rebound in overseas markets, which

accounted for 70% of its sales. Fearful of losing control of the

company Gould took over, cutting payroll from 4,700 to 3,100 and

another five plants were closed.

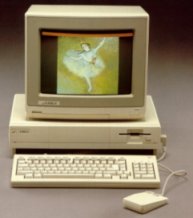

Around this time, Commodore launched their cut down Amiga, the

A500 that used the traditional Commodore all-in-one case design.

The Atari effort paled in comparison with Atari's fervent efforts

to sell their machine, even bundling over 30 games with it failed.

Commodore was back on top. The 8-bit market however, had turned bad

since Commodore released the Commodore 128. It used the Z80

processor as used in the Spectrum and had a '64 emulation mode.

However, it failed to catch on and bombed in the market place.

Commodore made their last foray into creating 8-bit technology,

only returning to create the unreleased C65

computer in 1990. Commodore was beating their competitors but there

was a sense of gloom, as Commodore seemed destined to fail

again.

By this time the Amiga has become the world's best selling home

computer, ever. On 24th April, the Amiga

3000 was unveiled, although you would not have known it as up

until 30 minutes prior to it's announcement, Commodore denied that

A3000 existed. There were also rumours of Kickstart 2.0. A huge

advancement on the Kickstart 1.3. Commodore became increasingly

confident that it could market anything as the set production of

two new machines. In June 1990 one of their most expensive mistakes

were released, the CDTV. It was designed

for the domestic market in an attempt to move the Amiga into the

living room. A questionable tactic in light of current events. Only

Sony's PlayStation has managed to shrug off the kids' image and

become a desirable item for the general public through a huge

amount of advertising. Considering Commodore's problem the CDTV had

no chance. Sales persons were disallowed from mentioning the Amiga

in the same sentence as CDTV, and the machine had to be kept away

from Amigas. Even the Philips competitor, the CDi failed after a

five-year attempt at moving into the market.

Commodore began to make serious financial mistakes. In August of

that year the A500+ was released. It

was basically an A500, but contained the

ECS chipset and Kickstart2. It was on sale for only six months

before being preceded by the A600. The A600

was basically an A500+ in a smaller box. An embarrassment, seeing

that the A1200 was also released in 1992.

During 1992 the Commodore management scraped a number of

projects that could have bought the Amiga to the fore once again.

The Amiga 3000+ was put on show, an expandable version based upon

the A3000 it had AGA graphics. It was later scrapped, and released

in a totally revamped form as the A4000. On September 11th 1992 the

Amiga 1200 was unveiled. Whilst it was still a prototype, being

plagued by CPU-intensive transfer across the IDE and PCMCIA ports,

Commodore insisted that it go into the shops as it was. Meanwhile

the C64 had entered its final phase as an serious alternative to

the Amiga. Software support had begun to dry up (although not as

much as on the Amstrad and Spectrum) and the system was being sold

cheaper and cheaper. At one point it was being sold for £50

for the basic system with an optional 1541 disk drive. Commodore

magazines were awash with rumours on the C65 system that had come

to light as it looked as if Commodore was about to release it.

Eventually Commodore announced they were concentrating on the Amiga

platform, leaving their own range of Commodore 8-bit behind. Whilst

they were not dead yet, it was clear that the ride would only last

for a little while. It lasted longer than anyone expected - Future

Publishing's Commodore

Format remained in business for a further three years,

disappearing in September 1995.

As 1993 began, the company tried a last ditch attempt to save

everything they had worked for. Their share value had dropped to

just 5 dollars per share and there was an air of gloom surrounding

the company. However, they would not go down without a fight and

were preparing their second attack at the console market in the

form of the CD32. They had learnt from the

CDTV mistake, actually calling it an Amiga

whilst improving the specs to match the A1200. Things were looking

up, games were slowly being released for the console although these

were mostly ports of Amiga titles and polls placed the CD32 as the

most popular CD-based system during 1993 and 94. However, cracks

began to appear at Commodore as their parent company began to lay

people off. The advanced AAA chipset had been shelved and work had

begun on a new chipset called "Hombre" that was to be based upon a

HP-RISC processor. According to journalist Stuart Campbell, once

managing director of Amiga Power, a meeting was held involving all

of the major games companies, in which it was decided that the

Amiga was dead, and that software development should be wound down.

In April of that year it was announced that the A1200 had broken

all previous records, with 100,000 sales since it's launch. The

Falcon, Atari's 32-bit computer had failed to attract the public

being largely incompatible with the Atari ST. A dark cloud was

looming over Commodore.

1994: The bow breaks

Doom and gloom surrounded the Amiga camp. The PC was moving into

the home playing games that the Amiga could only dream of at the

time. Whilst Amiga magazines were attempting to create an sense of

optimism even they were appearing strained. Most countries had an

Commodore company that was financially independent of the parent

company- one by one these went into liquidation with one of the

first being Commodore Australia. In March Commodore posted huge

losses. On April 22nd, they had laid off most of their staff at the

parent company, Commodore International. By April 25th only 30 of

Commodore's 1000 employees remained and two days later the West

Chester facility was closed. The storm that had been rumbling in

the distance for so long was about to begin, and it threatened to

take Commodore and the Amiga with it.

On Friday April 29 at 4:10 P.M. Commodore filed for liquidation.

Their announcement was short

| Commodore International Limited announced today that

it's Board of Directors has authorized the transfer of assets to

trustees for the benefit of its creditor and has placed its major

subsidiary, Commodore Electronics Limited, into voluntary

liquidation. This is the initial phase of an orderly liquidation of

both companies, which are incorporated in the Bahamas, by the

Bahamas Supreme Court. This action does not affect the wholly-owned

subsidiaries which include Commodore Business Machines (USA),

Commodore Business machines LTD (Canada), Commodore/Amiga (UK),

Commodore Germany, etc. Operations will continue

normally. |

If Commodore's liquidation had seemed like the death of a foster

parent, the death of a real parent turned out to be even more

painful. On June 20th, 1994, Jay Miner, the father of the Amiga

died at the El Camino Hospital in Mountain View. He had been

fighting against illness for a while, and eventually died from

heart failure due to kidney complications.

The previous year had seen each individual Commodore company

drop like flies until only one remained- Commodore UK run by David

Pleasance and Colin Proudfoot. In January, Chelsea Football club

considered taking legal action against Commodore for unreceived

sponsorship money. A futile action as it turned out. The management

at Commodore UK announced their buyout plan for Commodore and the

Amiga. However, many predicted that the Amiga would never survive

this setback as Amiga World, the first Amiga magazine was canceled

on the 1st of March, 1995.

Almost a year after the Commodore liquidation the battle for

their remains were fought. Commodore UK had withdrawn from the

fight due to a lack of financial muscle and it eventually fell to

two PC manufacturers, Dell and Escom. Whilst Escom had made it

clear that they only wanted the Commodore name, the liquidators

refused to separate the two forcing Escom too bid again. Dell had

offered $15 million, but there were several conditions attached,

including a 30 day extension to review the inventory available.

This was unacceptable for the liquidators who wanted to sell

Commodore as soon as possible and so it went to Escom for $14

million, a German company that was the second largest PC

manufacturer. $4 million of this related to CBM and $10 million

related to Commodore International Bahamas, Ltd. an affiliate of

CBM. The former CSG operation located at 950 Rittenhouse Road in

Norristown

PA was purchased by GMT Microelectronics Corp., a company formed by

former CSG management in order to purchase the chip-making assets.

The purchase price was $4.3 million plus another $1 million to

clear EPA liens. Assets included the plant, equipment, other

inventory items at that location.

Escom separated the two names Commodore and Amiga into two

subsidiaries, Commodore became Commodore BV and Amiga became the

property of Amiga Technologies, run by a former Commodore man,

Jonathan Anderson. The Commodore name was put to use again as it

adorned a new range of Pentium PCs installed with Windows 95, as

well as a range of speakers, CD racks, and mouse mats. The

reasoning behind this being that Commodore were still well

respected for the range of PCs.

Amiga Technologies on the other hand suffered a slow death as

Escom starved them of development and staff. Apart from licensing

the technology, designing a new logo, bringing a fresh supply of

Kickstart 3.1 ROMs to the market, and prototyping the awful Walker

system, very little happened. During June 1996 Escom filed for

liquidation, with many blaming the Amiga curse as the reason.

Whilst the cost of buying the Commodore assets may have

contributed, 1996 was also the time when the bottom dropped out of

the PC market as systems suddenly dropped in price. Ready-built

computers halved in price in a matter of months contributing to

their financial situation as well as a number of boardroom antics

that made investors nervous. As part of a mass reorganization,

Amiga Technologies announced they

were to be sold to Viscorp, one of the

Amiga licenses to face a future as a set-top box. Fortunately (or

perhaps unfortunately for some), Viscorp dropped out of the running

during October 1996 due to dire financial troubles and died. Their

dream of an Amiga set-top box remained unfulfilled as the Amiga

supporters in the company quit and the Amiga press abandoned them.

Their time had passed and the Amiga was destined for bigger

things.

On March 27th, 1997, Gateway 2000, another PC manufacturer

stepped in and bought all rights to the Amiga. An entirely new

subsidiary is setup with Amiga Technologies being renamed Amiga

International. Development on new Amigas featuring entirely new

processors loom ahead and its return to the limelight is underway

once again. For Amiga the storm damage maybe repaired. To find out

what happens next in the Amigas fortunes click to the history of the Amiga page.

Commodore: The New Breed

The Amigas' future looked bright under the

Gateway leadership, promising new convergence boxes. However, the

Commodore name remained a bad omen, leaving a series of

bankruptcies in its wake. A management buyout by Escom Netherlands

resulted in the Commodore subsidiary who renamed themselves

Commodore NL. The company had little connection to

the original Commodore brand, used solely as a brand for the sale

of Commodore-labelled PCs. The Amigas' future looked bright under the

Gateway leadership, promising new convergence boxes. However, the

Commodore name remained a bad omen, leaving a series of

bankruptcies in its wake. A management buyout by Escom Netherlands

resulted in the Commodore subsidiary who renamed themselves

Commodore NL. The company had little connection to

the original Commodore brand, used solely as a brand for the sale

of Commodore-labelled PCs.

True to their namesake Commodore NL did not last long, filing

for liquidation less than a year after Escoms' bankruptcy. The

company's assets were bought by Tulip (a Dutch PC manufacturer) on

Wednesday July 2nd 1997 for an undisclosed sum (read the press release). The move, according

to company officials, would allow them to increase PC production

and sales up to 1 million per year. It is unlikely that this

prediction has come true. However, the company has been able to

make money through brand licensing. In a series of events that

mirrored its Amiga counterpart, Tulip licenced the Commodore name

to several third party manufacturers. This resulted in the

appearance of numerous Commodore-branded office items (paper

shredder, anyone?) and two attempts to recreate a 21st century

equivalent to the cheap-and-cheerful Commodore 64.

Commodore 64.... again!

On August 26th 1998, after five years of absence, Web Computers

unveiled a new version of the old favourite. The new machine bore

little resemblance to the original, utilising MS-DOS as the primary

operating system and emulating the original CBM 64 through a

software emulator. Ironically the C64:Web.It is aimed at a market that the Amiga

had previously attempted to secure with Amiga's failed MCC set-top

box.

This was followed in 2000 by the licensing of the Commodore

trademarks by >Computer National Inc. for their range of

desktops. Like Web Computers, they also promise the development of

a true successor to the C64/128,

based upon an 'all-in-one' wedge design. An interesting

continuation of the Commodore brand that may produce great things

if it is marketed towards the low-end convergence market. Of

course, long-time Commodore users will be aware that marketing has

remained a novelty to any company that has bore the Commodore

name...

Local Links

Commodore: the second Amiga owners

C64:Web.It

Commodore Evolution

More information

Tulip - current owner of the

Commodore trademarks

Amiga - current owners of the

Amiga

Gateway - fourth

Amiga owners

BACK

|